While traditionalists surely looked quizzically at the contemporary portraits that Barack and Michelle Obama commissioned for display in the National Portrait Gallery, one could count on The Washington Post and The New York Times to explain how wonderfully revolutionary the Obamas were to promote African-American painters to overturn the "bland propriety" of white traditions.

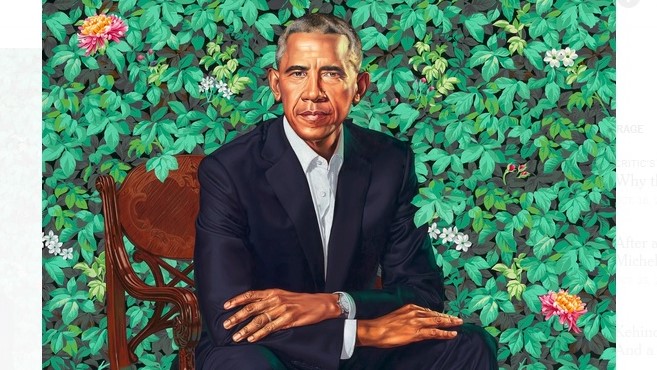

Kehinde Wiley placed a pensive President Obama in a thicket of plants. Amy Sherald pictured Mrs. Obama with a gray skin (her trademark look) and an expansive dress.

Kehinde Wiley placed a pensive President Obama in a thicket of plants. Amy Sherald pictured Mrs. Obama with a gray skin (her trademark look) and an expansive dress.

Washington Post art critic Philip Kennicott's review was headlined "The Obamas’ portraits are not what you’d expect and that’s why they’re great." He said "The two portraits render their subjects life-size, which underscores their historical importance and accomplishments."

Kennicott insisted "a stroll through the National Portrait Gallery emphasizes that fact in a visual and emotional way that recalls not just the racism built into this country’s founding document, but the racism that has shaped the history of art and portraiture since the Renaissance." He concluded:

The Obamas’ potential to change the tone and political culture of this country was blunted by the persistence of that racism before and during their time at the country’s political apex. Now that they have left office, now that their fundamental decency is in high relief by contrast with the new political order, memory is refreshed. They look a bit older than the two people who carried so much collective fantasy of a different America with them to Washington nine years ago. That fantasy was premature and unrealistic, and it is only now clear how powerfully it animated the meanest impulses of those who reject it. But these portraits will remind future generations how much wish fulfillment was embodied in the Obamas, and how gracefully they bore that burden.

New York Times art critic Holland Cotter was mostly pleased:

Mr. Wiley depicts Mr. Obama not as a self-assured, standard-issue bureaucrat, but as an alert and troubled thinker. Ms. Sherald’s image of Mrs. Obama overemphasizes an element of couturial spectacle, but also projects a rock-solid cool.

It doesn’t take #BlackLivesMatter consciousness to see the significance of this racial lineup within the national story as told by the Portrait Gallery. Some of the earliest presidents represented — George Washington, Thomas Jefferson — were slaveholders; Mrs. Obama’s great-great grandparents were slaves. And today we’re seeing more and more evidence that [under Trump] the social gains of the civil rights, and Black Power, and Obama eras are, with a vengeance, being rolled back.

On several levels, then, the Obama portraits stand out in this institutional context, though given the tone of bland propriety that prevails in the museum’s long-term “America’s Presidents” display — where Mr. Obama’s (though not Mrs. Obama’s) portrait hangs — standing out is not all that hard to do.

Cotter also mused that "Whereas Mr. Obama’s predecessors are, to the man, shown expressionless and composed, Mr. Obama sits tensely forward, frowning, elbows on his knees, arms crossed, as if listening hard. No smiles, no Mr. Nice Guy. He’s still troubleshooting, still in the game."

At least Cotter expresses a mild dissent against the Michelle Obama painting, hoping for something more “bold” to prefigure a future national political career: "To be honest, I was anticipating — hoping for — a bolder, more incisive image of the strong-voiced person I imagine this former first lady to be, one for whom I could easily envision a continuing political future."