Argentine-born Communist revolutionary and guerilla leader Che Guevara murdered and imprisoned thousands, supervised firing squads during revolutionary tribunals, founded forced labor camps, and dissolved free press in Cuba.

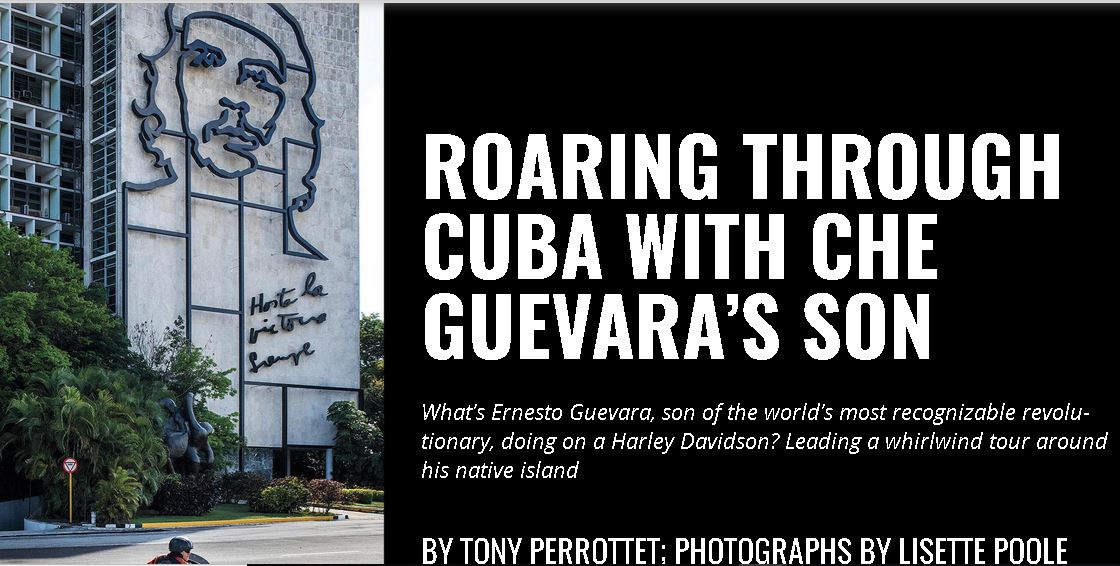

Bizarrely, none of that made it into Tony Perrottet’s shallow, symbolic travelogue of Revolutionary Cuba that appears for some reason in the November 2019 edition of Smithsonian, the official journal of the federal-funded Smithsonian Institution: “Roaring Through Cuba With Che Guevara’s Son What’s Ernesto Guevara, son of the world’s most recognizable revolutionary, doing on a Harley Davidson? Leading a whirlwind tour around his native island.”

(Hat-tip to the Babalu Blog for first taking apart the piece.)

Perrottet has previously praised Cuban dictator Fidel Castro in the New York Times in two articles, comparing him to Frank Sinatra and James Dean. For the Smithsonian piece, he palled around with Che’s son, bopping around the island to various shrines to the mass killer (and lousy father to boot)

As every Cuban school kid knows, Santa Clara was the site of Che’s greatest victory during the Cuban revolutionary war of 1956-9. It was then the crossroads of the island’s transportation system and a key strategic goal in the armed rebellion led by Fidel Castro against the U.S.--backed dictator Fulgencio Batista....

As Humberto Fontova noted at the Babalu Blog, the only time the word “dictator” crops up in a story about the mass murderer Che is in reference to the Batista regime that preceded the Communist dictator Castro:

The bikers roll out of Cienfuegos, site of a 1957 rebellion by navy officers against the Batista dictatorship.

The author performed a spiritual pilgrimate for Che the killer:

We filed into an attached museum, which told the story of Che’s extraordinary life, starting with his childhood in the Argentine city of Rosario in the 1940s and his move as a medical student with matinee idol good looks to Buenos Aires.... There were also images from Mexico City in 1955, where the peripatetic Che met Fidel, an idealistic young lawyer-turned-revolutionary, at a dinner party. The two had opposite personalities -- Che a soulful, poetic introvert, Fidel a manically garrulous extrovert -- but possessed the same revolutionary zeal....within 25 months, the odd couple were in control of Cuba, with Che given the job of overseeing the execution of Batista’s most vicious thugs.

Che didn’t stop there, of course.

....Che would write tender poetry for his wife, and when he departed for the Congo in 1965, left tape recordings of his favorite romantic verse, including Pablo Neruda’s Goodbye: Twenty Love Poems. He also left a letter for his four children to be opened and read only in the case of his death.

....

Having written a book about the Cuban Revolution, I was a little star-struck myself and lapped up shreds of Guevara family gossip....the austere and disciplined Che worked long hours, six days a week, first as the head of the National Bank and then as minister for industry. On his day off, he volunteered as a laborer in the cane fields, a nod to Mao’s China....

Perrotet tried to rationalize his disappointment at not being able to see his hero’s private study:

But perhaps that’s as it should be, I suddenly realized. Their father had been for so long the world’s collective property -- his life poked and prodded, his every written word pored over, his mausoleum in Santa Clara a tourist attraction visited daily by busloads of people -- that the family might want to keep one place private, just for themselves.

One of the sparse bare hints of an imperfect life came here:

As for me, I’d read volume after volume about Che’s peculiar character while researching my book on Cuba, studying his mix of romanticism and icy calculation, his monkish self-discipline, his caustic humor and infuriating moralizing. But learning about his family life had added another dimension, and an extra level of sympathy. Che followed his revolutionary mission with a determination that impressed even his many enemies, but he also wrestled with inner doubts, and knew what he was sacrificing....the image that lasted from the trip was from the museum in Santa Clara, where the photograph showed Che smiling as he fed the baby Ernesto with a milk bottle. It’s a contradiction the kids have had to make their peace with. I thought of what Ernestito had told me with a shrug: “Che was a man. You can see the good and the bad.”

But Perrottet offered up none of the bad -- the reality -- of Che Guevara’s life, only a pro-Communist whitewash in the Smithsonian's journal, with pictures.