With all the headlines about “fake news,” the liberal media elite don’t have a perfect track record, either. Reporter Jayson Blair concocted stories for the New York Times back in 2003, while Stephen Glass fabricated numerous pieces for The New Republic in the late 1990s.

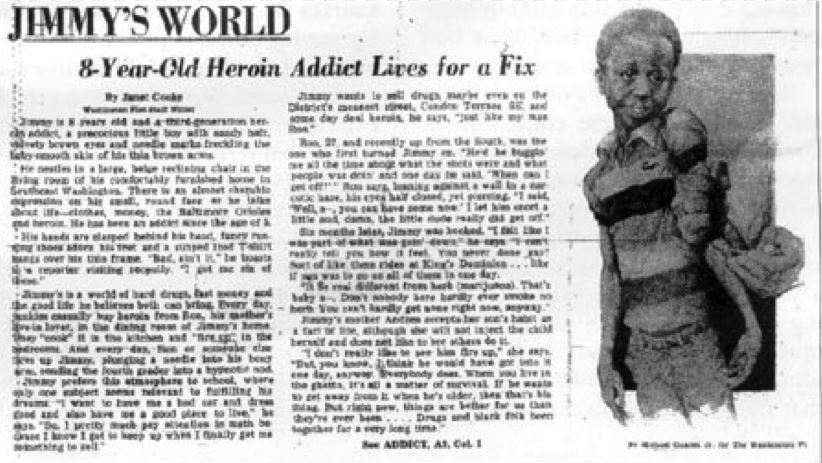

To be sure, these were not deliberate efforts by the publications themselves to mislead readers, but frauds perpetrated by ambitious writers who sought an easy path to journalistic fame. The most notorious scam of this sort was the 1980 front-page Washington Post article by reporter Janet Cooke headlined “Jimmy’s World: 8-Year-Old Heroin Addict Lives for a Fix.” The article was distributed by the Post’s syndication arm and re-printed in hundreds of local newspapers. The fraud was uncovered only when Cooke was awarded a Pulitzer Prize the following spring.

To be sure, these were not deliberate efforts by the publications themselves to mislead readers, but frauds perpetrated by ambitious writers who sought an easy path to journalistic fame. The most notorious scam of this sort was the 1980 front-page Washington Post article by reporter Janet Cooke headlined “Jimmy’s World: 8-Year-Old Heroin Addict Lives for a Fix.” The article was distributed by the Post’s syndication arm and re-printed in hundreds of local newspapers. The fraud was uncovered only when Cooke was awarded a Pulitzer Prize the following spring.

It wasn’t just that readers were given fiction instead of fact. After the story appeared, D.C. police and social service agencies mobilized enormous resources to find the boy at the center of the story, while coming under heavy criticism for their alleged “massive failure” in not knowing about the boy before the Post story appeared. And one mother blamed the Post story for triggering an overreaction by authorities that temporarily cost her custody of her young son.

For those who don’t remember, here’s how it went down, as chronicled in Post articles retrieved from Nexis, starting with an excerpt of the story that appeared on September 28, 1980:

Jimmy is 8 years old and a third-generation heroin addict, a precocious little boy with sandy hair, velvety brown eyes and needle marks freckling the baby-smooth skin of his thin brown arms.

He nestles in a large, beige reclining chair in the living room of his comfortably furnished home in Southeast Washington. There is an almost cherubic expression on his small, round face as he talks about life — clothes, money, the Baltimore Orioles and heroin. He has been an addict since the age of 5.

...

Jimmy’s mother Andrea accepts her son’s habit as a fact of life, although she will not inject the child herself and does not like to see others do it.

“I don’t really like to see him fire up,” she says. “But, you know, I think he would have got into it one day, anyway. Everybody does. When you live in the ghetto, it’s all a matter of survival. If he wants to get away from it when he’s older, then that’s his thing. But right now, things are better for us than they’ve ever been....Drugs and black folk been together for a very long time.”

The outrage was immediate, with police launching an effort to find the child and rescue him from these dire circumstances. A September 30, 1980 front-page article in the Post recounted how local authorities took the report seriously and mobilized their resources to respond:

D.C. Police Chief Burtell M. Jefferson said yesterday that he has ordered a wide-ranging search for an unidentified 8-year-old Washington youth whose heroin addiction and life-style were described in a newspaper article Sunday.

...

Lawyers for the Post, citing First Amendment provisions of the U.S. Constitution, have refused to disclose the information.

...

Carolyn Bowden, supervisor of the Department of Human Services, said that since 9 a.m. yesterday, her workers had made hundreds of telephone calls and received hundreds more, most from persons expressing “shock and terror.”

DHS personnel were scouring neighborhoods of Southeast Washington, but “so far, we’ve had no success,” Bowden said. “If we don’t hear anything by this evening, we’re going to appeal to radio stations to broadcast an appeal for anyone with information to call us 24-hours-a-day, or call the police.”

“I believe the child’s life is in danger, I really do,” Bowden said. “Bear in mind, he’s only 8 years old. He’s said to be small. If the drugs aren’t given in the correct dosage, I’d say he’s in real danger. This newspaper article could be the child’s epitaph.”

That same day, columnist Richard Cohen said the Post article was evidence of a system that had failed:

I do not know either how a reporter can find her way to an eight-year-old who is an addict but the police do not know. How is this possible? How is it possible that the drug enforcement people with their trillions of dollars in federal aid and their computers and their police officers did not know of this kid — could not do what a reporter could do?...

Somewhere in all this is a story of failure — of massive failure. Somewhere in all this is a story of agencies not caring or not doing their jobs, of money being spent on the wrong things, of schools not paying attention, of well-meaning but defeated teachers who cannot cope and, also, maybe just as important, neighbors who knew or suspected and didn’t do a thing. Somewhere in all this are a lot of questions that the city, the school system and the mayor ought to answer. An eight-year-old boy is about to die. Somebody, for crying out loud, ought to care.

<<< Please consider helping NewsBusters financially with your tax-deductible contribution today >>>

The following Sunday, October 5, 1980, Cooke shared a byline with staff writer Lewis Simons in another front-page piece that credited four other Post staffers with assistance. Included in the story was a — presumably false — passage that suggested new interviews with friends of “Jimmy.”

Children in the area close to Jimmy’s age know him and of his involvement in drugs. “He’s bad,” says one 11-year-old who adds he doesn’t have the “same s---” Jimmy uses, but “I can get some bam (preludin)...” Another boy, 10, says of drugs, “I don’t see nothing wrong if you be feeling good and make some cash, too. Me and my friend can get you some herb if you need it.”

But local authorities, having no luck finding the child, called off the search and expressed doubts that he was real. According to an October 16, 1980 Post article:

Mayor Marion Barry said yesterday that city officials are giving up on their search for an unidentified 8-year-old heroin addict whose life style, including daily injections of the drug, was the subject of a Washington Post article last month.

“We are kind of giving up on that,” Barry said when asked about the comprehensive search for the youth, known only as “Jimmy.” Barry said that city officials decided that the boy’s life would be endangered if the heroin dealers and users who frequented his home thought the boy might talk to authorities.

...

Barry said that he and police department officials are convinced that the Post report, including a description of the boy being injected with heroin by his mother’s live-in lover, is at least part fabrication.

“I’ve been told the story was part myth and part reality,” Barry said. He said that after talking to police narcotics officers, and from his own personal knowledge of the drug world from his days as a community organizer, “We all have agreed that we don’t believe that the mother or the pusher would allow a reporter to see them shoot up.”

Washington Post editors said yesterday that the newspaper stands by its story.

On November 28, 1980, the Post carried the account of a woman who blamed the “Jimmy’s World” story for a judge’s ruling costing her custody of her young son:

A D.C. Superior Court judge yesterday placed a 5-year-old boy in court custody and prosecutors accused the child’s mother of neglect after a police officer testified that unexplained traces of barbiturates were found in the child’s blood and mysterious needle marks on his arms.

After the hearing before Judge Sylvia Bacon, the mother, Mary Thompson, wept in the court corridor. “I haven’t given my kid any drugs,” she said. “This is ridiculous. Is this what justice is all about? I can’t believe this is happening.”

...

In an interview last week, Thompson attributed the city officials’ actions to fear of child abuse that was spawned by an article in the Washington Post on an 8-year-old heroin addict, identified only as “Jimmy.”

“That’s why they’re on me,” she said. “Because of Jimmy.”

It took more than six weeks, until January 16, 1981, before Mrs. Thompson regained permanent custody of her son. The judge ruled there was insufficient evidence after an expert disputed the lab results showing barbiturates, saying the results would have suggested the child was nearly comatose, but he was actually “quite active and alert” when he was initially examined.

Then in April 1981, six-and-a-half months after it first appeared on the Post’s front page, Cooke won the Pulitzer Prize for her story. Almost immediately, the Pulitzer committee discovered Cooke’s academic credentials were not what she claimed, and Washington Post editors grilled her about the story. Within two days, the award was withdrawn and Cooke finally admitted to her editors that “Jimmy’s World” was a fiction.

According to the account in the April 16, 1981 Post:

Cooke now acknowledges that she never met or interviewed any of those people and that she made up the story of Jimmy based on a composite of information about heroin addiction in Washington gleaned from various social workers and other sources.

Her admission followed revelations that certain statements she had made in an autobiographical report to the Pulitzer authorities also were false. Cooke had said that she was a magna cum laude graduate of Vassar College and held a master’s degree from the University of Toledo. In fact, she attended Vassar for her freshman year and received a bachelor of arts from the University of Toledo.

Cooke resigned from the Washington Post yesterday.

“It is tragedy that someone as talented and promising as Janet Cooke, with everything going for her, felt that she had to falsify the facts,” said Benjamin C. Bradlee, executive editor of the Washington Post. “The credibility of a newspaper is its most precious asset, and it depends almost entirely on the integrity of its reporters. When that integrity is questioned and found wanting, the wounds are grievous, and there is nothing to do but come clean with our readers, apologize to the Advisory Board of the Pulitzer Prizes, and begin immediately on the uphill task of regaining our credibility. This we are doing.”

Later in the piece, the paper revealed how some there had doubts about Cooke’s story, even as they were publicly standing by her reporting:

She and City Editor Milton Coleman drove to the neighborhood in Southeast Washington where Cooke had maintained that Jimmy lived. Cooke was unable to find Jimmy’s house. Back at the Post, several editors examined the file of notes Cooke took when reporting the story and listened to several tape-recorded interviews she had done with drug experts. There were no notes of Cooke’s first supposed encounters with Jimmy and his family. But some of the notes and the tape-recorded interviews indicated that “Jimmy’s World” could have been a composite of the lives Cooke heard about from the experts and social workers.

That Sunday, April 19, 1981, the Post published an exhaustive (18,000 word) autopsy of how the false story had made it into print. The paper’s ombudsman, Bill Green, called it a “journalistic felony.”

So why did it all happen? And how? Milton Coleman and Bob Woodward try to take the blame, and well they should. They had primary responsibility. But to place all the burden on them is a huge mistake. There’s enough blame to go around.

Ben Bradlee, the executive director, was wrong, and Howard Simons, the managing editor, was wrong. Beginning, of course, with Janet Cooke, everybody who touched this journalistic felony — or who should have touched it and didn’t — was wrong. It was a complete systems failure, and there’s no excuse for it. These are brilliant people. The Post newsroom runs over with high-caliber talent and skills that weren’t employed.

And columnist Richard Cohen, who six months earlier had used the story to slam the supposed failures of local authorities, admitted being fooled:

It was such a good story, the editors wanted to get it into the paper. They wanted this so badly, they waived the rules about names and places, overlooked the warning signs, and the story went into the paper. And when it was printed, it created such a fuss that a columnist like myself, wondering why a pusher would talk to a reporter, and wondering even more why he would shoot up some kid for free, wrote about it anyway. It was such a good issue, such a wonderful controversy. I, too, wanted to believe.

Fifteen years later, Cooke gave a lengthy interview to GQ magazine, explaining how it happened. The Post summarized her interview in a May 9, 1996 piece by then-media writer Howard Kurtz:

In Cooke’s view, she did not invent “Jimmy” to win a Pulitzer or make a big splash; she was just desperate to get off the Post’s Weekly staff, which she described as “the ghetto.” Cooke was also trying to get away from her Weekly editor, whom she despised.

After an employee at a Howard University drug program told her an 8-year-old was being treated there, Cooke mentioned it to [then-city editor Milton] Coleman, who declared it a front-page story and urged her to find the child. She could not.

“I kept hearing Milton telling me to offer total anonymity,” Cooke recalled. “At some point, it dawned on me that I could simply make it all up. I just sat down and wrote it.”

Like all other human endeavors, news organizations are made up of human beings, some of whom are inevitably going to be liars and con artists. As the Post’s Bill Green correctly noted in his investigation 35 years ago, the lesson from a story like “Jimmy’s World” is not to blindly trust reporters, but insist on documenting the facts:

This business of trusting reporters absolutely goes too far. Clearly it did in this case. There is a point when total reliance on this kind of trust allows the editor to duck his own responsibility. Editors have to insist on knowing and verifying. That’s one of the big reasons they hold their jobs.

Readers should have the same attitude: you can’t just trust that the news on a Web site or social media, or in your local paper or on television, is true. An honest news story will support its conclusions with factual details that can be verified elsewhere, whereas fake news will include quotes or facts that won’t withstand scrutiny.

The Janet Cooke story reminds us that fake news can come from any source. Of course editors need to do their best to stop such falsehoods from ever being printed, but at the end of the day, it’s up to readers to read the news with a critical eye, and satisfy themselves that it’s the real deal.